An Extensive Planning Guide for Desert Hikes – Part 2

Introduction

In Part 1 of this blog posting series, we covered the aspects of planning a desert hiking trip at home. We discussed the different tools and techniques that are available and also covered the important aspects to keep in mind while planning the route. We now know how to use Google Maps, Google Earth, OpenStreetMap for our purposes and know the strengths & weaknesses of the different tools.

In this Part 2 of the series, we will go through the steps to actually use the prepared track out in the field. What are the tools that are available? What specifics need to be considered? I will guide you through my setup step-by-step. Again, same disclaimer in Part 1:

Disclaimer:These are my thoughts - based on my skills and knowledge I brought along from previous trips. So use this information carefully - if you have questions, get in touch, I’m happy to help out if I can. Perhaps approaches and techniques below work for me but do not work for you.

Outdoor Aspects of Mobile Devices

While in the past you had multiple hardware devices, often one for each purpose, you have it all consolidated today into the smartphone. For outdoor aspects, this helps a lot since you simply save weight and space. Personally, I can not recommend to invest into a specific GPS hardware anymore since you can cover the same requirements with your smartphone as well - even with better capabilities such as better quality maps, easier handling etc. and you save space, weight and money. There might be some specific cases where this does not count, but I didn’t come across any of those situations so far. Check out this article in case you want to get a different opinion.

However, there is one major issue with smartphones: they are greedy for electricity. This problem even gets worse due to the multiple ways the smartphone could be used on trips: you listen to music, you use it as a GPS, you … so the battery life is limited. During weekend trips, this shouldn’t be a big deal, but when you spend weeks in the desert with hardly a possibility to recharge your device, you need to have a plan.

Therefore, you have basically two possibilities (or a mixture of both): a) limit the usage of the mobile device b) make sure you have enough power supply

For my desert hikes in South America I applied a mixture of both which I want to explain quickly below.

1) Limiting the usage of the mobile device

I didn’t use my smartphone for anything else than handling documents and using it as a fine-grained GPS navigation device (more on this further down). Music, camera, flashlight etc. were all separate devices with a separate need for energy. This helped me a lot to limit the usage of the smartphone and hence the need for energy. Furthermore, I was running it constantly

- with low display light as much as possible (Don’t use adaptive/auto brightness)

- in energy saving mode (available for iOS and Android),

- in flight mode (you should not expect any cellphone coverage anyway)

- without any vibration alarms on

- with shutting down each app after having used it. By doing so, I was able to keep my battery alive for multiple days without even shutting down the smartphone.

2) Make sure you have enough energy supply

The good news is: there is plenty of energy supply in the high deserts of South America due to the fact that clouds are very rare in winter time. This characteristic most probably counts for plenty of other deserts on this planet. With the support of a solar panel and a powerpack, you have basically an endless source of energy (during the day) with which you can charge your devices (during the night). I had a specific priority order for charging the devices at night (don’t leave your batteries outside your sleeping bag!): first the satellite messaging device, then the smartphone, then the rest. This is a risk-based decision - the most critical devices need to be charged first.

So the solar panel is definitively a key item in the high deserts in South America since the natural circumstances are perfectly made for it. However, I doubt that this is the right item for a 1-week trip in cloudy environments where you cannot make full use of it. According to my experiences, solar panels are often an overestimated item that do not deliver against the expectations since the natural circumstances are often simply not given (enough sun). So most probably the alternative solution via powerpacks is better, but also more expensive.

Document Management

Google Drive offers free cloud storage and apps for multiple mobile devices in order to store the data in the online cloud or offline. I specifically used Google Drive to store map information, trail information, word docs, flight details, link pages etc. offline and by doing so, have it available offline even if you are far away from any Internet connection. Via Google Drive / Google Docs I also wrote my trail notes offline into a text file and synchronized it with the cloud when I popped out of the desert.

Google Drive is the solution I used - I don’t see any difference with using iCloud, Microsoft OneDrive, Dropbox etc. - at the end they just should offer an offline capability. (I should note in this moment that I do not recommend to upload privacy sensitive data to any of these cloud services in an unencrypted way.)

Offline Navigation in the Field

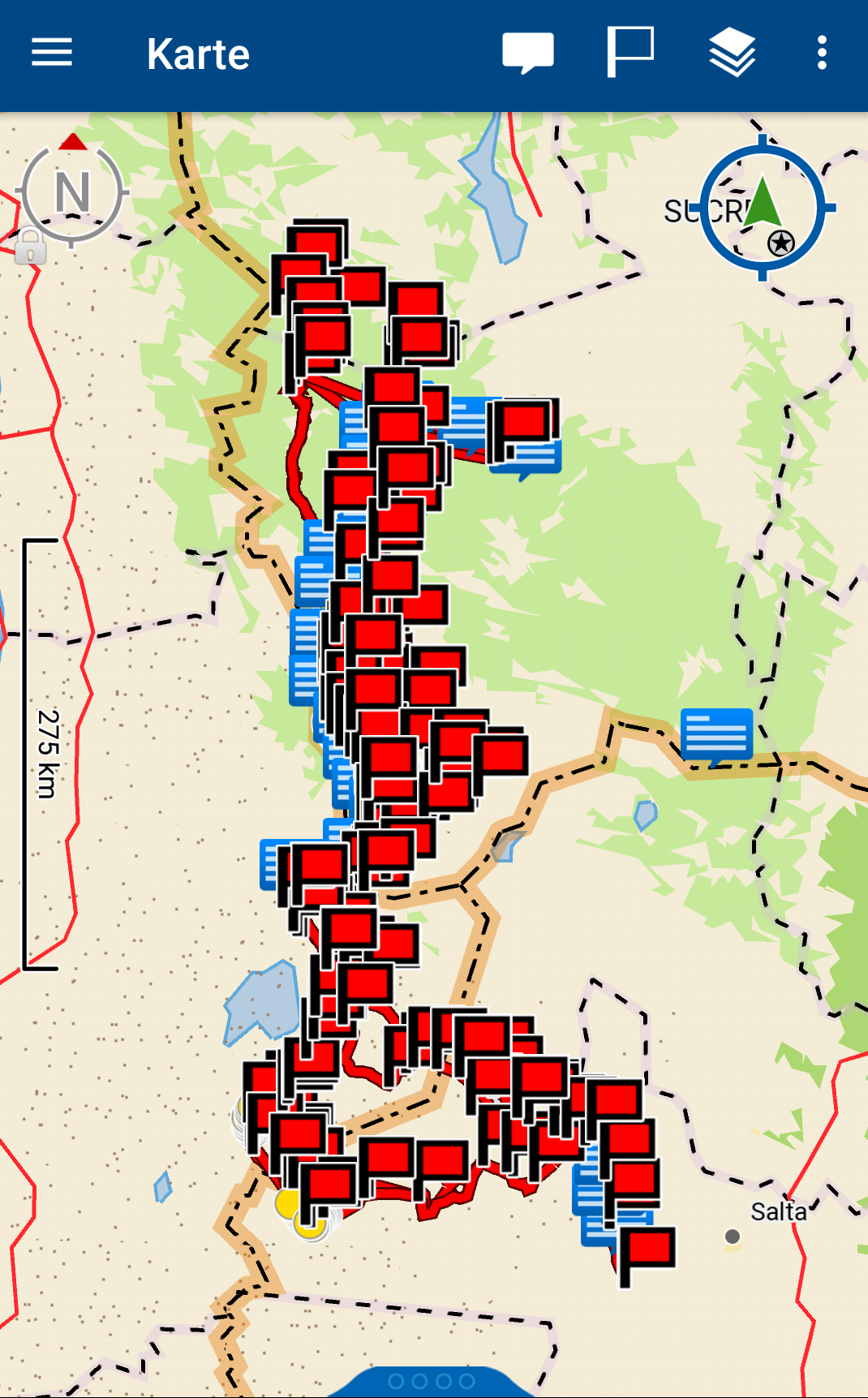

As mentioned above, I primarily use my smartphone for GPS-based navigation in the field. I leave the discussion which app is best suited for these kind of intentions to other authors. Personally, I’m a big friend of GAIA which led me without issues through several outdoor destinations in South America during the last years. I haven’t found a scenario that GAIA was not able to handle properly.

GAIA App

As most of the mobile device apps nowadays, GAIA offers the possibility to synch your device with the GAIA cloud service. This means, you can organize and manage your tracks via the web interface on gaiagps.com - then just synch your phone with your account and you have them all stored locally. This is extremely helpful if you have need to make some changes to your routes during travel - you simply log into your account from a device, do your changes and synch with the app later on. Afterwards, you can pick a map layout for viewing the tracks offline.

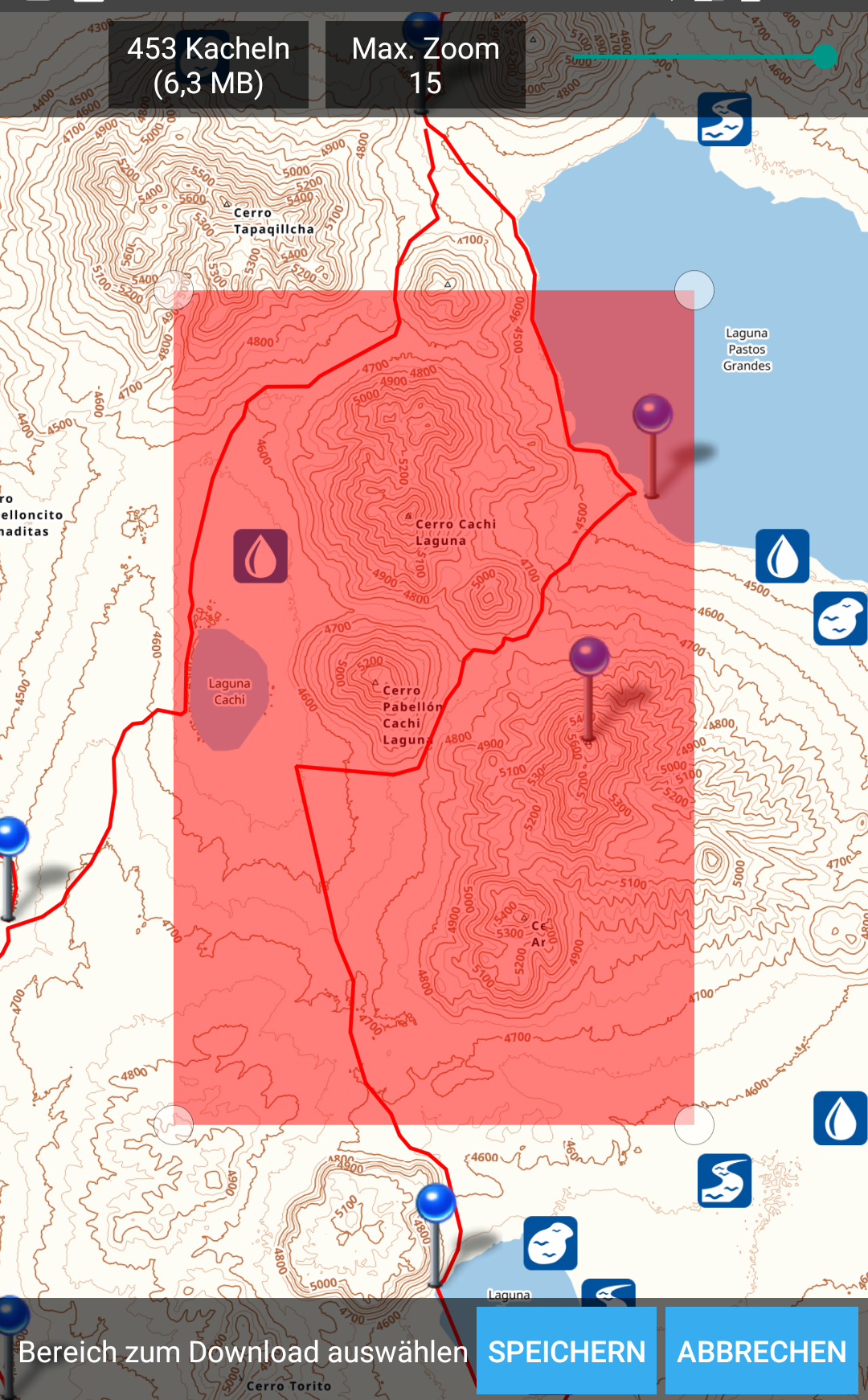

Once this is done, you can download the specific area of the track you intend to follow offline. By doing so, you have the map details offline on your phone and can use all details in the field without a connection needed. Amazing feature! Even better, you can define the zoom detail and decide on your own how much details you need - be aware that these steps should be done before you are somewhere with a bad WiFi. Downloading fine-grained maps takes time!

There are myriads of articles on the Internet on “how can I put map X on device Y” via special hacks and workarounds. These days are gone with Gaia - so I can definitively recommend GAIA for offline navigation out in the wild. Check out some tips here for importing Google Earth Images into GAIA. The folks from sectionhiker have some more detailed introduction for the proper usage of the GAIA app, have a look here. Also, Luc made a nice video demonstrating the route planning with Google Earth and GAIA - watch it here.

DeLorme Explorer (old) & DeLorme App

Delorme has been bought by Garmin

I have to admit, I’m a big DeLorme fan. It’s a great device that you can use for traveling to remote places with a backup plan in case things go wrong – which gets even more severe when you go solo. However, I don’t want to cover the basics of the DeLorme here. I intend to explain more how I used the DeLorme on a daily basis for navigation purposes. Please be aware that I own the old DeLorme Explorer, the one available before DeLorme got bought by Garmin. So the one without an extended GPS capability built in. I don’t know anything about the new one.

First of all, I used the smartphone for fine-grained tracking and planning only. For the daily rough navigation I used the GOTO-function of the DeLorme since it was in constant tracking mode anyway. This means, it sent a tracking point to the central server via satellite connection each 30 or 60 minutes which worked perfectly for me. Additionally, I had the complete planned tracks synched with my DeLorme as well - so basically a backup of the synch with smartphone via GAIA. This gives you additional safety since you do not solely rely on your smartphone. Keep in mind: electronic devices can break (anytime!) especially if you leave them out in the cold during -15 degrees at night.

So why using the DeLorme for rough navigation? It was turned on anyway and was designed to survive for 4-5 days when fully charged. This saves battery for your smartphone.

Printed Maps

There are definitively reasons why you want to bring printed maps with you like in the good old days. As said, electronics can break and in case you don’t have any backup plan for these cases, things could end up badly. This is just one argument why people still use offline, printed maps.

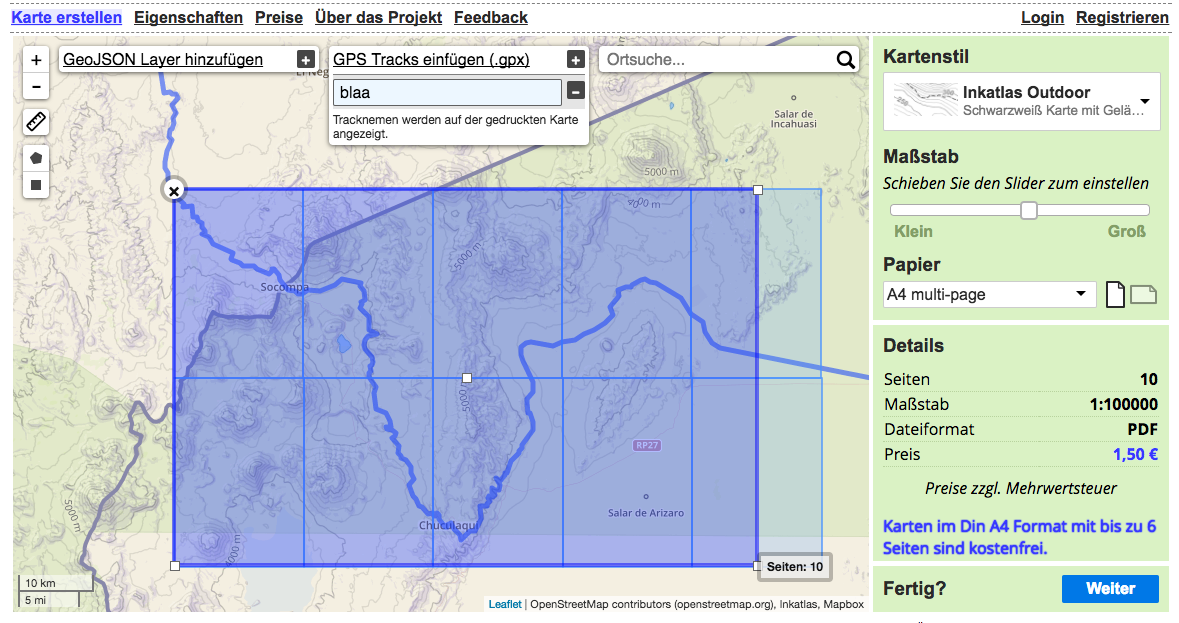

My favorite service for these cases is Inkatlas.com - it’s an amazing service which creates you printable PDFs for GPX tracks you upload. You simply upload your GPX file, pick a map layout, select the parts of the map you basically intend to print and define the level of detail you want. That’s it.

There are further possibilities to print maps - a summary can be found here.

Conclusion

In Part 1 and Part 2 of this series, we covered the different aspects of planning a long distance desert hike, based on the example hike in the high deserts of South America.

It’s interesting how technology has changed the way trips today get planned and prepared. 20 years ago the situation was completely focused on offline work without the capabilities of Internet-based apps and tools. Although technology has made it easier to plan challenging hikes, things are different when you face mother nature out in the wild. Perhaps all your prepared tracks, routes, ideas and plans suddenly face a different setup - never forget that things look different when you are sitting behind a computer screen.

“Everyone’s got a plan until they get hit.” – Joe Louis

Hence, I recommend to get familiar with the tools first, plan and execute afterwards some smaller trips in a more safe environment where mistakes can easily be handled. This is an important step before you go out to areas where you totally rely on your own actions and decisions made during the planning stage. Using these web-based tools and techniques is a skill, the same as being able to fish, to hike, to raft or to bike. So skills need to be trained and exercised in order to be mastered.

Check out the bikepacking community and their ideas about planning trips properly - yes, they have 2 wheels and can cover greater distances but they face similar planning issues like us. Additionally, I can highly recommend to have a look at the blog series from Luc about “Data-Driven Trip Planning” in case you want to get another opinion about planning extended outdoor trips.

Finally - keep in mind that the world out there could look different - as John le Carre, British author, once said: “A desk is a dangerous place from which to view the world.”